Going Viral -- in the small

On October 25, 2010 a young woman, who was a member of MoveOn.org, attempted to have a picture of herself taken handing an 'offensive' sign to Rand Paul as he was entering a hall for a candidate debate in Kentucky. She did not succeed. An organizer knocked her to the ground and stomped on her head. A local TV station caught the action and broadcast it in their news program. The video migrated from there to YouTube, and a firestorm erupted on Twitter. Shock, disbelief, anger, and dismay were expressed at the picture of the young woman being stomped in the head. That evening there were 944 Twitter messages about the incident. All expressed concern over what our politics is becoming. The rest of the week there were messages about the identity of the person doing the stomping and what would happen to him and then expressions of approval as he was charged with assault.

On the 26th a somewhat different theme was voiced.

Teabaggers scream for Freedom of Speech, then grown men curbstomp a woman who doesn't agree with them. #dontstomponme #kkkwithoutthehoods

RT @MoveOn: Speak out against right-wing tea party violence. You can't stomp on us! http://bit.ly/9IM2vI

"You can't stomp on us!," "#dontstomponme" are expressions of defiance. These two streams would eventually, October 29, be joined by #dontstomp. These messages are a different tone from most of the messages. "Don't tread on me" as an assertion of defiance is available to everyone in our society, and this event called it forth one more time.

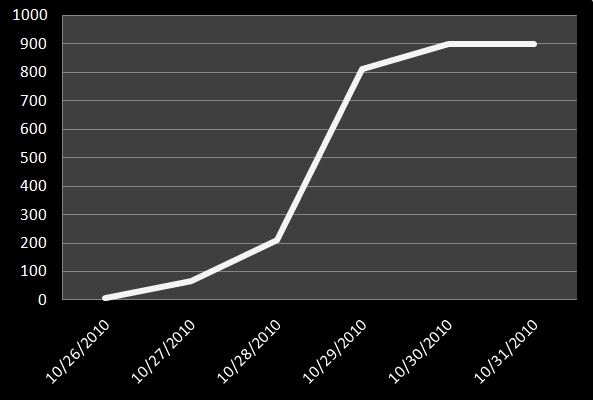

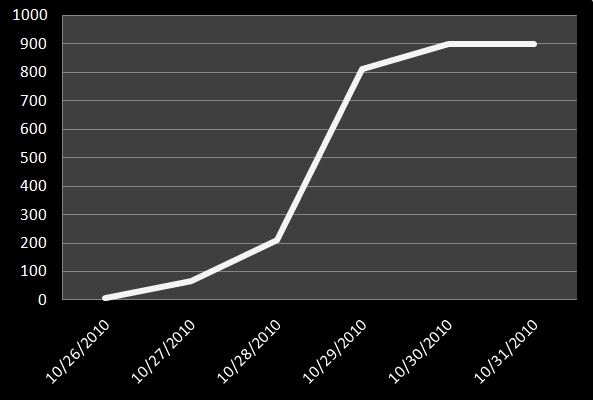

The number of messages was not great. Nine hundred and one contained one or more of these three messages distributed over a five day period. The cumulative distribution in time is shown in the figure.

|

I am going to argue that one can see going viral in the dynamics of this stream of messages. There are two principal conceptions of 'going viral.' One is about quantity and the other is about process.

Going viral as quantity is about starting small and increasing to very large. Of course, 'large' is a highly conditional term. It is conditional on one's expectations. The interpretation of stock market movement, for example, is full of expectation talk. The economy was expected to grow 2%, it grew 3% and the stock market went shooting off into the stratosphere. Three percent is 'big' only in terms of the expectation of two percent. Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert organized a rally in Washington D.C. and planned for 60,000. They adjusted upward to 150,000. Then 215,000 people showed up. That is big! Is 901 big? Since I have observed streams of Twitter messages at 20,000 a day 901 seems small to me. That is why "in the small" is in the title. But there might be another expectation by which it would be big. Whatever conception of 'big' one uses needs to be justified when characterizing a stream as having gone viral.

Going viral as process is about the interaction in the stream. The classic case, from which 'viral' is taken, is an epidemic. A few people have the 'it.' They come into contact with others to whom it is distributed with some probability. Since each person is assumed to come into contact with more than one person and the probability of distribution is high the second 'wave' should be larger than the first. And you continue that process until you have run out of eligible contacts. That process tracks in time in the same way as the numbers in the figure above. But the distribution in time is the result of a process of 'mixing' of a specific character. That is the character I want to identify in the Twitter messages containing one or more of the three phrases.

The logic goes like this: One person posts a message. Others read the message. It 'takes' for some who retweet it. And that retweet becomes available to others who read and either retweet or not. Since there is only one original post the message is likely to be read by only a few. Some will retweet and the message will be seen by a larger number than for the first tweet. Repeat until no one is left. In this logic the start is small and grows slowly. At some point the number retweeting and the number of their followers takes a sharp upward turn. And eventually there is no one left who is interested enough to retweet. And that is the cumulative distribution in time in the figure.

Retweeting is a procedure invented by users of Twitter to forward a message by quoting with attribution. The form is RT @[username] [original message]. When a message is retweeted it goes to all of the followers of the person who did the retweeting. Thus, it is a way to spread a message. The message is posted, someone reads it and retweets, the message is then available to all of the followers of the retweeter and to anyone who would find it by searching.

Retweeting activity in the streams asserting defiance is quite different from standard practice. In a recent study Sysomos collected 1.2 billion tweets for analysis and found that only six percent of them were retweets. [Sysomos, Sept 2010] In the 901 messages in this stream 698, or 77%, were retweets. While this is quite different from the standard practice it is not unique for political use of Twitter. Almost all political streams have more than 6% retweets, but the top quintile is 47% to 77% putting this collection right at the top of political streams.

Retweeting is exactly the process of mixing that can lead to going viral, but the mixing is not limited to retweeting. I will show two examples of how the mixing proceeds in this stream.

The first example is 'classic' retweeting.

RT @MoveOn: Speak out against right-wing tea party violence. You can't stomp on us! http://bit.ly/9IM2vI

The person, Changeagent26, read a message posted by MoveOn, added RT @ and sent it forward. This was the first retweet of the original message found in my search. The time was 8:17 pm October 27, and the url links directly back to MoveOn.org. There were a total of 182 messages like this beginning the evening of the 27th and running through 9:50 am October 29. Forty-seven were on the 27th. Two were on the 29th. The rest were on the 28th. One message becomes 182 retweets that are then forwarded to all of the followers of the persons doing the retweeting. The message from MoveOn.org 'took' in a big way.

The second mixing is theme and variation.

#DontStompOnMe because I don't think the country is run by Muslim socialist Nazi. I think its run by the smart black dude... #p2 #tcot

#DontStompOnMe because I see racism/sexism/homophobia in the world. I'm not "hyper" sensitive. I'm just "regular" observant. #p2 #tcot

#DontStompOnMe because I find @SarahPalinUSA more annoying and less informed than 3 Snooki's & a Kardashian. #p2 #Tcot

#DontStompOnMe because I can still vote from a hospital bed, loser. #p2

#DontStompOnMe because I think Fox News has as much integrity and educational value as Wacka Flocka Flame... #p2 #tcot

#DontStompOnMe because I don't share your love of billionaires, bigots, boobs, and Beck. #p2 #tcot #teaparty

There were many more than this, but the theme and variation is clear. The theme is"#DontStompOnMe because"; it is the common element in these examples and in the 213 uses of this theme. Then one 'fills in' after the initial phrase with whatever is your favorite expression of disagreement with the thinking leading to the stomping. Eleven of the 213 were on the 30th; the rest on the 29th. The messages were arriving very rapidly between 11:00 am and 1:00 pm on the 29th, and it picked up again between 9:00 pm and midnight. The mix of the messages in the stream and the contiguity of new variations appearing are clear indications that people were reading some and making up their own that then was retweeted by others.

The logic of retweeting fits nicely with going viral understood as a process. If you look for retweeting you may well find going viral. But going viral depends on the stream continuing in time. In the Sysomos study they also found that 92.4% of all retweets happen within the first hour. It is pretty hard to get something we would think of as going viral when messaging lasts for an hour or less. The example I worked with here is three days, which is not very long, and that is another reason for "in the small." But it does go on for more than an hour.

Microblogging politics is different from standard practice in many ways. This is one of them. There is more interaction in the political messaging. In that sense it is communication rather than only self expression.

© G. R. Boynton

November 4, 2010