A Story About George Robert Boynton, Sr.

by G. R. Boynton, Jr.

We do not drink the same water so it must be in the genes. It is the year 2002 and Anna Cary Bassett Boynton is nine and one half years old; one-half is very important when you are only nine. She visited Wales when she was five, and she has been on the go ever since. In addition to Wales, she has been to England twice, Honduras, this summer she will return to England and go from there to Germany and Switzerland. Egypt and Turkey are just over the horizon. My mother and father lived and traveled the world. I have always thought travel a wonderful elixir for a life mostly spent in front of computers. My children, Anne and John Robert, take international travel as a right. Anna? It's no big deal. World travel is just what you do; it is so much a part of your life that you take it for granted

|

|

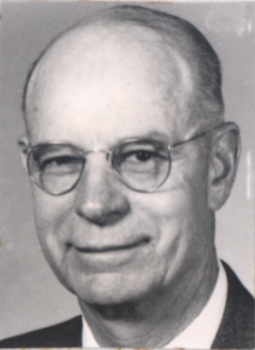

George Robert Boynton, Sr.

|

One way to tell my father's story, then, is -- how you get from a tiny town in central Texas to four generations of world travelers.

Bellville is a tiny town in central Texas. It is not very far from Austin. It is not too far from Houston. There have been no Boyntons in Bellville for a long time; his mother died in 1946, which is the last time Boyntons were there as far as I know. I remember a town with dusty gravel roads right up to my grandmother's house; the streets of the town were paved with gravel. She lived in a rather large house that was desperately in need of a paint job. It had a front porch with a swing -- as did they all. The small hill on which it was built sloped down and away from the road, and the house was on stilts at the back. It was not very far off the ground. Just high enough for young boys, my brothers and me, to climb under and find a cool respite from summer heat. My father carried one piece of that home with him throughout his life. Behind the house was a pasture for cows. It had been a long time since there had been a cow there by the time my grandmother died, but that heritage followed him for life. He might travel the world, but he always came back to milking a cow.

He grew up in this tiny town. His father. George Amos Boynton, was a watchman for the railroad in a town that was otherwise almost wholly agricultural in economy and lifestyle. He graduated from high school, and then he did something quite unusual. He went to college. Today, when more than forty percent of high school graduates go to college, going to college does not seem unusual. But he graduated in 1924; in 1924 less than ten percent of high school graduates went to college. But he did, and he never went home again. How could he? He went to Rice Institute, as it was known then, to become a chemical engineer. The demand for chemical engineers in Bellville was negligible. Going away to college was the first step into a wider world. I did the same. My children did the same. My students at the University of Iowa do the same. He was just ahead of his time.

In 1928, when he graduated from Rice, chemical engineer was a fortuitous choice of careers. Oil was booming; it was especially booming in Texas. So he took a job with the Sinclair oil company working at a refinery in Houston. Oil was one of the few industries that boomed during the great depression. He survived well enough to help his younger brother go to college and to have a son in the middle of the depression. Just as the depression was ending along came World War II. Chemical engineers working in oil refineries were too valuable to go off to war. They were already doing the most they could for the war effort. We lived in Houston through the great depression and World War II.

I have always assumed that my parents would have lived out their lives in Houston or working for Sinclair if Sinclair had decided to move him -- except for his heart. He had a serious heart attack in an age when they knew a lot less about hearts than they do today. The doctors said -- stress. You have to quit the job you are in and find something with more exercise and less stress. He was 46. What do you do if you have to find a new career at 46? The answer was: a bookstore in a small town in central Texas where he could have a cow -- after a decade or so of being too busy for a cow. My parents loved to read. And they thought they would like small town life after twenty years in the big city. It would prove to be an important move. They found that you could not make a living with a bookstore. But he found the air force just 15 miles away. He started to work cutting weeds; that was for more exercise. But cutting weeds did not pay very well, and there were three college educations to pay for. So he started engineering for the air force. And that became a second step into a wider world.

We were not long for Lockhart; just long enough for me to meet the girl of my dreams. Then my parents were off to Cheyenne, Wyoming, Colorado Springs, Colorado, and the world. Once they got started they kept right on going.

They wanted to go to Germany, but you could not get to Germany working for the Air Force without paying your dues. The dues were a year and a half in Tripoli, Libya. That was before the days of Muammar Ghadaffi, of course. There was a U.S. air force base in Tripoli, and he was responsible for maintaining the runways. That meant he worked closely with local contractors. Given the history of Libya, the language of choice was Italian. So he learned Italian or enough Italian to get along. And he discovered that he was a quick study when it came to languages. Libya was not like Texas. A villa with a wall and a guard were the required living conditions. Not only was it exotic it was also a great jumping off point for traveling north Africa and the middle east -- travels mother has recounted in her remembering those years.

After the dues were paid it was off to Germany. Another Air Force base and another runway to maintain. And lots of opportunity to travel.

We traveled together twice. In 1964 I completed my ph.d. and, with their financial assistance, we headed for Europe to travel with them. John Robert celebrated his fifth birthday in Morbach, Germany. He got a six month head start on his niece, Anna, who did not make it abroad until she was five and one-half. At the time Anne was only a gleam in her mother's eye. I remember the village in which they lived. They had been living there for several years, but it was my introduction to European style shops -- lots of small shops specializing in bread or meat or other delights. And you could get everywhere on foot, I remember bruechen, the very clean lines of Bern, and going through the mountain from Switzerland to Italy. That was an incredible change of scenery in a very short distance. I also remember the run down hotel at which we stopped to spend our first night in Italy. The people working in the hotel spoke only Italian. The tourists spoke only English or German. And my father, who by this time had picked up enough German to manage, served as translator. He was the only one who could speak Italian, German and English.

More than a decade later, in 1978, we traveled together again. John Robert was grown -- a high school graduate -- and had spent the year living with a family in Germany. Anne was now a young teenager. It was a pretty elaborate trip for us involving Italy, Germany, Scotland, England and Amsterdam. Mother and dad were visiting Oxford, and they met us in Yorkshire -- from which all Boyntons come. We were not there very long. Long enough to see Burton Agnes, Boynton and Bridlington. We spent the night in a bed and breakfast in a tiny little town. Then we got on the ferry to Amsterdam, and my parents went on with their own sightseeing.

When my father retired the first thing he and mother did was to sail half way around the world and back. It was like all ocean travel -- mostly watching water go by. But they loved to read. It was a tanker with only a few passengers and good food, and it took them to Hong Kong. Then they turned around and headed for West Fork, Arkansas. West Fork was an inexpensive house and plot of land where he could have a cow. It was just outside of Fayetteville so they could share in the cultural advantages of the University of Arkansas. They went to Costa Rico for a year. They went to Guatemala to visit Douglas, my brother. They went to Uruguay. Then they went back to West Fork to stay.

One morning my father woke up, said good morning, and fell into a coma. He had traveled the world, but he died, at 78, in a tiny town where he could milk a cow. He lived from tiny town to tiny town -- with the whole world in between.

None of us has emulated his love for cows, but we have all found his inspiration as a world traveler a model for our own lives.